On October 7, 2024, the HDFF staff attended a seminar hosted by the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University – Institute of Security and International Studies, which discussed the trends and trajectory of Japan’s security policy in the Indo-Pacific.

Summary and key points

- Japan’s foreign affairs strategy went from passive checkbook diplomacy to active extended cooperation ;

- Even if public opinion supports Japan’s increased defense capacity, amending Article 9 of the constitution is not a question for now ;

- Being active in peacekeeping operations helps the county fill in the operational gaps ;

- Japan is still figuring out its orientation in balancing strategic alliances between ASEAN countries to establish itself as a third path in the region and minilateralism with Western countries.

Speakers:

Dr. Prakorn (Pop) Siriprakob – Dean of the Faculty of Political Science at Chulalongkorn

Dr. Akima Umezawa – Minister, Embassy of Japan

Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak – Professor and Senior Fellow of the Institute of Security and International Studies

Asst. Prof. Teewin Suputtikun – Lecturer at the Department of International Relations, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University

Dr. Pongphisoot (Paul) Busbarat – Director of the Institute of Security and International Studies and Assistant Professor in International Relations at the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University

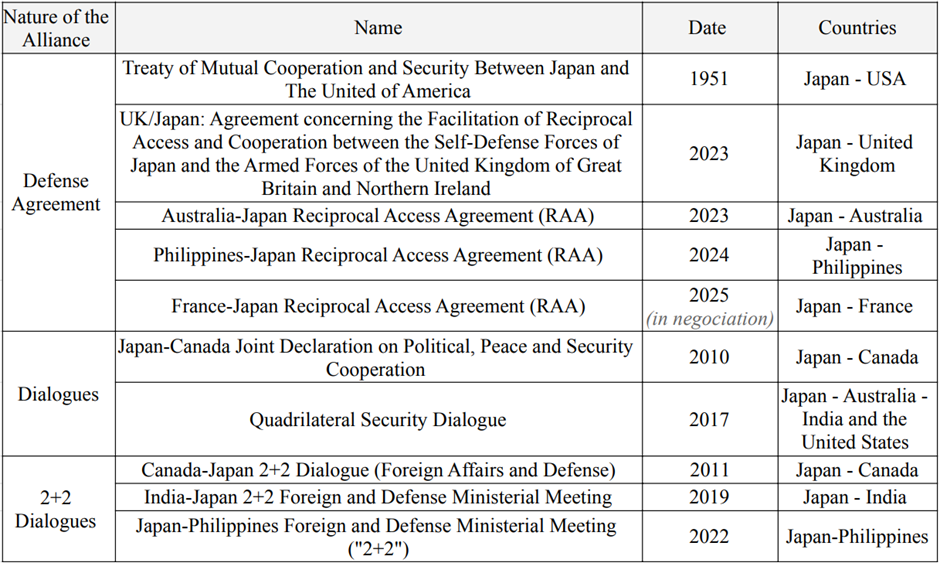

Dr. Prakorn (Pop) Siriprakob gave a welcome speech and briefly introduced the topic, he started by highlighting the increasing number of bilateral agreements Japan is currently developing and gave a short list of regional defense alliances it integrated recently. Those agreements and alliances show a paradigm shift in their foreign affairs policy. He then introduced the speakers and expressed how honored he was by Dr. Akima Umezawa’s participation in today’s roundtable. He closed the welcome speech by thanking everyone for attending the event.

Dr. Pongphisoot (Paul) Busbarat developed how the inauguration of the new Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is a milestone in the regional strategic dynamics as its leadership takes on a more assertive character. He shows determination to make his country a key player for stability and peace in the region in the upcoming years. Dr. Pongphisoot (Paul) Busbaratalso highlighted the ongoing contradiction –or at least the legal gray zone– between Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution which establishes the forever renunciation of Japan to war and the use of force in the context of ongoing active participation in more regional defense coalition treaties as well as active procurement of weapons and other military supplies.

Dr. Akima Umezawa gave a short geostrategic presentation on Japan. The country is surrounded by six neighbors (China, Russia, North Korea, South Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines), three of them are nuclear states and four of them are military powers. This regional context is exacerbated by growing tensions with neighboring countries. North Korea regularly performs missile tests and the Chinese and Russian Air Forces violate Japanese Airspace, which exposes Japan to direct potential threats and vulnerability regarding its closest circle of influence. The 2022 New Security Strategy (NSS) redefines how Japan will use mutual defense values to reach “regional pacifism”, a cornerstone of its foreign strategy. The NSS also identifies new actors, whether they are state actors or non-state actors, and addresses new challenges that need to be tackled such as economic and energetic security.

Dr. Akima Umezawa developed the Japanese position in Southeast Asia in order to understand how its middle-range neighbors perceive it, and the orientation of those partnerships. The Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), has been reiterated by Japanese former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida throughout 2023 and 2024. To that extent, Japan values not only its cooperation with Asia Pacific, but also shares the necessity to deepen its ties with its neighbors up to the Indo-Pacific because of its relevant strategic position nowadays. The goal is to enhance multilayer connectivity by increasing knowledge, law, and capacity exchanges. This should ensure the development of the public domain in the region. For the ASEAN-Japan 50 Years of Cooperation celebration, Fumio Kishida set the foundation rules to frame this cooperation: respect each other, recognize the diversity in culture and history, and enhance cooperation and dialogue.

. Japan’s FOIP originally had three pillars—promotion of basic principles, economic prosperity, and peace and security—but the new plan presents four pillars: (1) furthering principles for peace and rules for prosperity; (2) addressing challenges in an Indo-Pacific way; (3) building multilayered connectivity; and (4) extending efforts for security and safe use of the sea to the air.

Dr. Akima Umezawa proceeded to give an overview of the level of trust placed in Japan by the ASEAN states. He then compared these levels of trust with those placed in the US and the EU. Japan always has the first place in the ranking thanks to a long-lasting relationship of trust built on mind and heart. This heart-to-heart doctrine is a reminder of Japan’s determination to make trust a fundamental element of its diplomacy. For the near future, Japan holds a particular position regarding its good relations with ASEAN countries but also its close relationship with the United States of America. Considering its 4th position as the biggest economy worldwide, Japan aspires to be a third way in the region.

Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak reacted to Dr. Akima Umezawa’s presentation raising concern about the slow economic growth and the domestic situation. For him, those two factors decrease the possibility of establishing itself as a regional giant. The domestic situation should not be overlooked regarding the recent ministerial instability, which is even more true when political continuity is a requirement to be considered as a solid partner. Japan is torn in multiple directions to choose between building its defense, reaching a regional leader’s position, enhancing deeper cooperation with the US, or straightening its minilateral agreements as for the multiple regional defense agreements it recently ratified (cf. Table 1). By bringing those elements to the table he highlighted the necessity of understanding the regional perception of Japan to project short-term and long-term trajectories. This opens up the topic of the capacity of Japan’s autonomy on a regional scale.

Shinzo Abe, former Prime Minister (2012-2020) strongly promoted regional leadership through democratic values. This influence paired with the integration of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the ties with the North-Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was at the time very controversial and raised interrogation of Japan’s independence regarding Western ideologies.

Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak closed his intervention by asking other panelists what kind of country Japan wanted to be domestically and in the region.

Dr. Prakorn (Pop) Siriprakob pointed out the overlapping intermediary powers in the region and invites Asst. Prof. Teewin Suputtikun to develop more on the change of paradigm compared to the previous foreign affairs strategies of Japan.

Asst. Prof. Teewin Suputtikun draws attention to the significant changes in Japan’s position regarding its regional neighbors by tracking down its historical evolution. He describes the 1980s-1990s decades as a post-traumatic period. During that time, the government remained passive in its foreign relations and focused its dialogue mostly on checkbook diplomacy[1] by participating in development programs. In the 1990s, the country opened progressively to the world and became proactive in deepening its ties with its regional neighbors. These progressive changes have accelerated a lot over the last ten years but establishing defense principles and by changing its definition of “pacifism”. Japan got more and more internationally oriented with a stronger commitment to United Nations peacekeeping activities. By doing so, Japan is able to train its troops and keep up in terms of capacity building and training during peacetime. Recognizing the right of countries to defend themselves and adopting more politics to develop partnerships was a breakthrough from Shinzo Abe to enhance Japan’s reliability to its close partners.

In response to the rising regional tensions with the assertive behavior of China, the United States’ East Asian Policy from 2010 which relaxed the existing laws and regulations on weapons sales to Southeast Asia allowed Japan to improve its defense capacities. Japan and United States security cooperation predominantly targeted Taiwan directly as a protection mechanism where any attacks on the island would trigger a US intervention. Japan also developed a security agreement web with European countries endorsing the new Pacifism as ensured by military power and action.

Asst. Prof. Teewin Suputtikun highlighted how the most important priority went from economic development to development policies and more recently in the multilevel cooperation regarding environment or security. Regarding the bipartisanism of the shift, Japan is trying to remain neutral and avoid taking clear-cut positions.

Asst. Prof. Teewin Suputtikun also developed how the recent changes in the regional defense architecture becoming more uncertain making the population approve of government efforts to to prepare in case of military threats or attacks. However, for now, it is not a question yet whether they should amend Article 9 of the Constitution.

Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak approved the analysis on the mutation of the term pacifism regarding the regional and global context. For the first time since the war, the funds allocated to defense are significantly increasing.

Dr. Pongphisoot (Paul) Busbarat oriented the discussion on the Chinese perception of the Japanese shift, as those actions are sending clear messages, whether it is in terms of cooperation, allies, and by cascade effect, its position in the South China Sea.

Dr. Akima Umezawa approved and added that to ensure regional legitimacy, Japan must challenge China by adopting a firm stance as a defender of international law in the region.

Asst. Prof. Teewin Suputtikun warned that this kind of pro-rule of law and indirectly anti-Chinese rhetoric should be taken with caution, as it is more a war of public opinion than anything else. However, this does not prevent China from retaliating by recalling Japan’s bellicose past and also by emphasizing their rearmament and military aspirations. For him, one of the challenges today is to show that it’s not about accumulating power to be number one, but about making efforts to create a safer regional environment and to present itself as an alternative solution.

Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak developed Japan’s possibility for the future to establish itself as a key player in the region. First, he talked about deepening its relationship with the Philippines where there is also a strong material implication as well as a high level of cooperation due to both bilateral and multilateral agreements. Then he highlighted the opportunity for Japan to establish itself as a trusted partner in the region as a military power with no nuclear program. Most importantly, the Japanese government based its strategy on defending the rule of law and by spreading democratic values. However, these values are indisputably Western, and so it is vital that Japan grasps them and makes them its own to provide an alternative voice.

Questions

What is the current direction of the Japan-Thai relationship?

Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak answered that Thailand’s strategy has also changed recently and its ties with regional neighbors loosen down recently. Because of ministerial instability, Thailand could never leap to be a regional partner. It is very systematic for countries that lack stability to face some difficulty in establishing long-term partnerships. However, China might be one of the fewpartners of Thailand that remains stable and consistent in its orientation.

Other comments

Regarding the Chinese perception of Japan, Asst. Prof. Teewin Suputtikun argued how China is taking such a big spot in the international economy and the international community in general that it is very hard for Japan to find a proper space. For this reason, thinking Japan could make a comeback as the military power it used to be in the past is irrelevant and very unlikely. Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak added that nowadays, the whole region needs to tackle the nuclear situation of China. In this context, it is normal that Japan has to rely on American support and capacity.

Table 1. Japan’s Defense Alliances and quasi Alliances, Human Development Forum Foundation, 2024

[1] Checkbook diplomacy or chequebook diplomacy, is used to describe a foreign policy which openly uses economic aid and investment between countries to achieve diplomatic favor.

Comments are closed