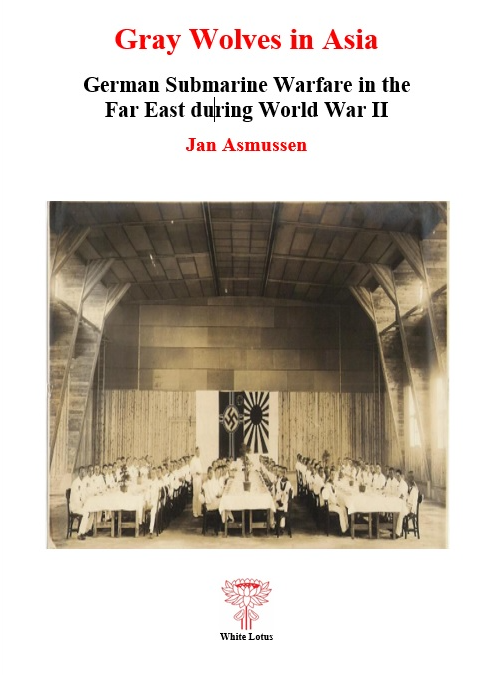

On March 6th 2025, the HDFF team attended the book launch of Gray Wolves in Asia: German Submarine Warfare in the Far East during World War II, written by Jan Asmussen, and hosted by the German-Southeast Asian Center of Excellence for Public Policy and Good Governance (CPG), in cooperation with the Asian Governance Foundation (AGF).

Speakers

→ Jan Asmussen : CPG Senior Research Fellow

→ Henning Glaser : CGP Director

While presenting his book, which explores German naval operations in East Asia during World War II, Asmussen argued that much of the literature on this period focuses on the European theater, leaving a significant gap in understanding Germany’s involvement in Asia, especially after the Battle of Midway. The session provided great analytical insights into these operations, examining strategic decisions, cooperation with Japan, and their long-term impact in the region

Following is a report from the book presentation and the discussion it sparked.

Germany’s naval strategy in East Asia

These efforts were part of a broader strategy to weaken Allied forces, but cooperation with Japan was constrained due to divergent priorities. While Japan sought German technological expertise, especially in air force and submarine production, Germany relied on Japan for vital resources like rubber and oil. Despite the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1936, which formally aligned the two countries, their strategic cooperation remained limited, and much of their joint operations were focused on material exchange rather than unified military action. This limited partnership was exemplified by the Monsun Group, which deployed German U-boats to the Indian Ocean, but their submarine transport operations were costly and inefficient, with only 3% of cargo capacity compared to more effective surface blockade runners, according to the author.

The German presence in Southeast Asia

Germany’s presence in Southeast Asia began in July 1943, when the first German submarine, U-511, arrived in the region. Germany established several key naval bases in Singapore, Jakarta, and Surabaya, with its headquarters in Penang. These bases served not only as repair stations but also as recreational sites for German sailors, many of whom had never left Nazi Germany before. Despite severe logistical challenges, these bases allowed Germany to maintain a naval presence in the region for the remaining of the war.

Naval Operations and Technical Cooperation

A significant part of Germany’s naval strategy was its reliance on Hilfskreuzer and blockade-running vessels, which were meant to operate more effectively than submarines. Meanwhile, Japan’s technical exchanges with Germany were primarily focused on improving air force and submarine production, leading to mutual assistance that helped to enhance both countries’ naval capabilities, albeit with limited success. After Germany’s surrender, some of these U-boats continued operating under the Japanese flag, serving as a reminder of the brief but intense collaboration between the two nations.

Post-War Developments

After Japan’s surrender, German personnel in Malaysia and Singapore were allowed to stay under an agreement with the Malayan forces, contributing to scientific research and assisting with local military efforts. Some German officers continued to support the newly formed Indonesian military, notably influencing the Declaration of Independence. The presence of approximately 2,000 German personnel in Japan until April 1946 was significant, with some civilians living in areas like Lake Kawaguchi, while others integrated into post-war Japanese society, marking the long-lasting cultural and historical impact of German influence in the region. What’s more, Asmussen’s findings, particularly through the correspondence of Uwe Röhling with his parents, revealed how exposure to Southeast Asian cultures altered the soldiers’ attitudes based on the interactions they’ve had there.

Discussion & Analysis

CPG Director Henning Glaser emphasized the importance of interpreting historical events not solely as military developments but also through legal and strategic lenses, underscoring how a broader perspective can truly enhance our understanding of their long-term implications.

The book presented Germany’s East Asian naval operations as a “footnote in history,” yet they still contributed to the broader war effort. The question was raised as to why German soldiers in the region did not continue fighting after Germany’s surrender, with Asmussen suggesting many had lost the ideological drive of the Nazi regime.

Participants compared Germany’s wartime strategic concerns with modern geopolitical issues, particularly the rise of China as a naval power. The effectiveness of submarines was debated, with some noting that modern submarines have vastly improved capabilities compared to those used during World War II.

Comments are closed