‘’Compassion fatigue can be described as the “cost of caring” for others in emotional pain’’ (Figley, 1982).

By: Judith Borren*

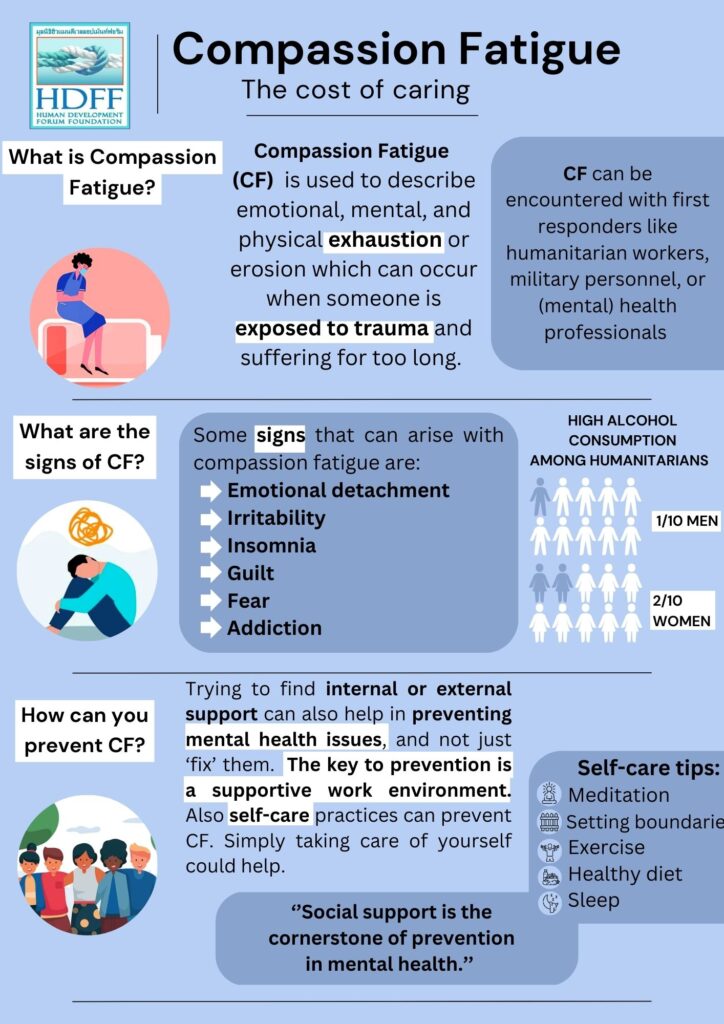

Overall, there has been a growing concern over the mental health of humanitarian aid workers, and other first responders in war and natural disasters. According to research, there is a link between this deteriorating mental health and the work in the aid industry.[1] First responders, amongst whom are humanitarian workers, are often exposed to stress and work with traumatized people.[2] These circumstances create a more stressful environment, can be overwhelming for aid providers, and can eventually cause burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress among aid workers.[3]

There are two types of secondary trauma to be distinguished: compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma. In short, vicarious trauma is the ‘’profound shift in worldview that occurs in helping professionals when they work’’. This can mean fundamental shifts in their beliefs about the world.[4] The International Organization for Migration stated that: ‘’Compassion fatigue (or vicarious trauma) is a reaction to the ongoing demands of being compassionate in helping those who are suffering’’.[5]

People often become aid workers because of the desire to care for and help others in need.[6] In the field as a humanitarian worker, you often encounter traumatic experiences of people or are directly confronted with them. So, what is compassion fatigue?

The term compassion fatigue can be used to describe emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion or erosion which can occur when someone is exposed to trauma and suffering for too long. Repeatedly hearing about and seeing suffering and trauma in the field can lead to changes in the psychological, physical, and spiritual well-being of humanitarian workers.[7]

Some feelings that can arise in people who are impacted by compassion fatigue are feelings of guilt, fear, and helplessness. Unattended to, and without a focus on mental health, this can lead to physical and mental health issues.[8] Awareness of the symptoms can help with preventing the issue from growing, in time to seek help. Signs of Compassion Fatigue include emotional detachment, irritability, insomnia, physical exhaustion, lack of motivation, and difficulty concentrating.[9] Vicarious trauma (a drastic shift in worldview) and compassion fatigue (emotional and physical erosion) can happen at the same time and can be cumulative.[10]

Something that is often neglected by aid workers is self-care, mentally and physically. However, self-care is of the utmost importance for managing a sustainable lifestyle, in which the aid worker can keep up their valuable role as a first responder, and at the same time focus on their (mental) health.[11] A big part of dealing with and preventing compassion fatigue is to ask for support and share emotions.[12] A strong support system can assist humanitarian workers in dealing with their emotions.[13] Also, physical, and more practical self-care can help prevent compassion fatigue, such as taking breaks and vacations, sleeping enough, eating healthy, delegating responsibilities, spending time in nature, and exercising. And lastly, building mental resilience can help prevent mental health issues. Building mental resilience can include setting realistic expectations for yourself, engaging in positive self-talk, and in activities you enjoy.[14]

Additionally, access to professional psychological help can be helpful. Unfortunately, mental health is often not a main priority for humanitarian workers and organizations. Trying to find internal or external support can also help in preventing mental health issues, and not just ‘fix’ them. ‘’Social support is the cornerstone of prevention in mental health’’.[15] The key to prevention is a supportive work environment.

Thus, some practical tips to address compassion fatigue according to a study conducted by the University of Washington include[16] Talking to someone you trust; this person can be someone at work, a professional, or a family member. Take care of yourself. As described above, self-care is often an afterthought for humanitarian workers, who are focused on helping others, and not themselves. Self-care includes eating well, sleeping enough, and taking time to exercise (even if it is a short walk). Another form of self-care is meditation. A study with aid workers in Palestine engaging in meditation has shown that a few minutes a day to meditate can make a real difference.[17] Furthermore, it is important to know your limits. You have to know when it is time to take it slow, and perhaps even take a break. You can help others better when you yourself are refreshed and have more energy. And lastly, focus on the good you are doing. Take some time to reflect, and notice that you are doing what you can for other people. Appreciate that.[18]

The key to long-term and sustainable humanitarian work lies in finding self-care techniques that work for you and developing them into a regular practice.[19] Untreated and unrecognized compassion fatigue can cause people to burn out or leave their profession, become addicted, or be depressed.[20] Not practicing self-care can have consequences for both you and the people you work with. Dealing with this trauma can be difficult, however, it is also a reminder of how important your work is. Making sure you are taking care of yourself is equally important.

*Judith Borren is a Research Fellow at HDFF.

[1] Plakas, Christina. “Burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress among humanitarian aid workers in Jordan.” January 2018.

[2] Bopp, Evert . 2023. “Mental Health and Burnout Risks for First Responders and Humanitarian Aid Workers.” Www.linkedin.com. January 11, 2023. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/mental-health-burnout-risks-first-responders-aid-workers-evert-bopp/.

[3] Christina Plakas,. “Burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress among humanitarian aid workers in Jordan.”

[4] Mathieu, Françoise . 2019. “Defining Compassion Fatigue, Vicarious Trauma and Burnout.” Tend. 2019. https://www.tendacademy.ca/what-is-compassion-fatigue/#:~:text=While%20Compassion%20Fatigue%20(CF)%20refers.

[5] Rohwetter, Angelika. 2023. “Compassion Fatigue.” Zeitschrift Für Psychodrama Und Soziometrie, December. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11620-023-00768-y.

[6] Angelika Rohwetter. 2023. “Compassion Fatigue.”

[7] Angelika Rohwetter. 2023. “Compassion Fatigue.”

[8] Evert Bopp, 2023. “Mental Health and Burnout Risks for First Responders and Humanitarian Aid Workers.”

[9] Evert Bopp, 2023. “Mental Health and Burnout Risks for First Responders and Humanitarian Aid Workers.”

[10] Mathieu, Françoise . 2019. “Defining Compassion Fatigue, Vicarious Trauma and Burnout.” Tend. 2019. https://www.tendacademy.ca/what-is-compassion-fatigue/#:~:text=While%20Compassion%20Fatigue%20(CF)%20refers.

[11] Evert Bopp, 2023. “Mental Health and Burnout Risks for First Responders and Humanitarian Aid Workers.”

[12] Angelika Rohwetter. 2023. “Compassion Fatigue.”

[13] Evert Bopp, 2023. “Mental Health and Burnout Risks for First Responders and Humanitarian Aid Workers.”

[14] Cameron, N., McPherson, L., Gatwiri, K. and Parmenter, N. (2020). Research Brief: Vicarious Trauma and Secondary Stress in Therapeutic Residential Care. Centre for Excellence in Therapeutic Care: Sydney NSW.

[15] ICRC. 2022. “Support & Innovation: Improving Mental Health for Humanitarian Workers – World | ReliefWeb.” Reliefweb.int. ICRC. May 11, 2022. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/support-innovation-improving-mental-health-humanitarian-workers.

[16] Perregrini, Michelle. 2019. “Combating Compassion Fatigue.” Nursing 49 (2): 50–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000552704.58125.fa.

[17] Pigni, A. (2014). Building resilience and preventing burnout among aid workers in Palestine. Intervention, 12(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1097/wtf.0000000000000043

[18] Perregrini, Michelle. 2019. “Combating Compassion Fatigue.”

[19] Cameron, N., McPherson, L., Gatwiri, K. and Parmenter, N. (2020). Research Brief.

[20] Perregrini, Michelle. 2019. “Combating Compassion Fatigue.”

Comments are closed